I will say this up front: I am not an expert birder. I like birds, I can identify most the ones that come through my yard, and when Matt quizzes me on bird calls as we're hiking, I have about a 50-50 chance of being able to say what that bird is.

That's why it's so awesome to occasionally go birding with people who really know what they're doing. There are many, many people in this area who can hear a birdsong and be able to tell you -- without seeing the bird -- what it is, how common it is, where it's been lately, whether it's worth looking for...and if it's worth looking for, they'll help you find it.

If you're not one of these people, consider going out birdwatching with one of these groups sometime, and see (and hear) what you're missing. (And if you are one of those people, please comment and let me know if I missed anything!)

Maryland Ornithological Society has meetings and field trips all over Maryland, including some in Rock Creek Park. Their September/October schedule is nine pages long!

Audubon Naturalist Society has free birding trips in the metro area and beyond. Also look through their catalog for paid classes and trips that focus on birds -- there are many.

Prince George's Audubon Society has regular walks on 1st and 3rd Thursdays at Lake Artemesia, and 1st and 3rd Saturdays at Patuxent River Park.

The Audubon Society of Northern Virginia has classes, programs, and field trips at local sites like Huntley Meadows, Riverbend Park, and many others.

The Northern Virginia Bird Club lists a couple of outings a week on their calendar as well.

The Nature Conservancy has free birding outings for members about once a week this fall.

This post is part of a series on birding resources...

Birding Resources Part I: Bird ID Books

Up next: Birding resources on the web & birding apps. Let us know if you have any recommendations!

Getting outside, inside the beltway: tips on getting outdoors in the Washington, DC area.

Most Popular Posts

-

Photo credit: ilkerender Last year we listed places to swim near DC and places to rent a canoe near DC . Today we return to complete the s...

-

Summer calls out for being on the water. We've found more than a dozen locations where you can rent a canoe or kayak in the Washington, ...

-

What a lovely break in the heat we're having. Here are some things to keep an eye out for in August. Links are to previous LOOK FOR post...

-

This spring has been cold and a little slow, like last year. Morels , in particular, are just starting to show up. Below are all the things ...

-

The Jack in the pulpits are starting to unfurl right now. I've always loved these flowers, showy in their design rather than their color...

-

I've been distracted from the Natural Capital but I haven't totally forgotten about you guys...Here are some of the other things we ...

-

This time last year, the wood frogs were out and had already laid their eggs. As of this morning, the pond where we always find them was com...

-

Our monthly roundup of things to look for this month: Photo credit: InspiredinDesMoines I originally wrote about bald eagles for t...

-

Two of the things we love best about living in the DC metro area are the public transportation system, and the parks. And so, one of our mai...

-

If I had to name my biggest frustration with the nature around DC, the lack of good swimming holes might top the list. Until 7th grade I liv...

Showing posts with label Birds. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Birds. Show all posts

Friday, October 18, 2013

Friday, February 15, 2013

Backyard Bird Count This Weekend

Here's all it takes to participate in this weekend's count:

- Look for birds for at least 15 minutes on February 18-21. You can count anywhere; it doesn't actually have to be a backyard.

- Keep track of the species that you see, and for each species, the largest number that you see together simultaneously.

- Enter the information on the GBBC website.

House Sparrow (66% of lists)

Passer domesticus

6.25 inches

If you've got a birdfeeder, you've got house sparrows. These birds were brought over from Europe sometime in the mid-1800s and have proceeded to make quite a home for themselves. Males have a lighter breast with black patch on their throat; females are plain and brown.

Cardinalis cardinalis

8.75 inches

There's something about a bright red bird that makes people happy. But female cardinals are pretty too: a hard-to-define mix of tan, red, and orange, with a bright orange bill. You'll often hear both sexes making short "chip" noises to check on each other.

Zenaida macroura

12 inches

What color is a mourning dove? A brownish-grey, with pink undertones in the breast and maybe some blue if the light hits it right. We almost always see them in pairs or groups, walking around in our yard or perched on the utility lines, where they show off their long tails. Their song is in fact mournful sounding.

Sturnus vulgaris

8.5 inches

This bird is another import that has become widespread. Every once in a while a huge flock lands in our yard to forage, then disappears again. Starlings are smaller than crows, and their beaks are longer and thinner. Juveniles are covered in small white flecks, which make a beautiful pattern.

Turdus migratorius

10 inches

Everyone knows the robin, but you can amuse your friends by learning the Latin name for this bird (my brother in law calls out "turdus!" every time he sees one). Some robins spend the winter in our area, so they're not necessarily a sign of spring -- though they do become more plentiful as it starts to warm up.

Picoides pubescens

6.75 inches

Downies are our smallest woodpecker. I was surprised to see this bird on the list as frequently as robins, but we do see them almost every day on our peanut bird feeder. Males have that red spot on the back of their head; in females it's just white.

Carpodacus mexicanus

6 inches

We used to have a pair of house finches that visited our windowboxes in Dupont Circle and delighted us with their sweet songs and the splash of color on the male's head. These birds are the third import on our list; they're native to the western US, but someone brought them east in the 1950s.

Poecile carolinensis/atricapilla

5 inches

Chickadees are the shortest, roundest birds on our list: fluffy balls of cuteness that fly from tree to tree looking for insects. Washington DC is in the overlap of the range of two hard-to-distinguish species; Carolina chickadees are smaller than their black-capped cousins.

Junco hyemalis

6.25 inches

Juncos are snowbirds -- and Washington is part of their southern winter home. When it warms up a little more, they'll be off for Canada. For now, look carefully for these grey or grey-brown birds on the ground: they can blend in quite sneakily. (See our full post on juncos)

Zonotrichia albicollis

6.75 inches

White-throated sparrows are another winter resident of the DC area. If one thing surprised me more than seeing the tiny yellow patches on this sparrow's head for the first time, it was learning that it's named for the white patch just under its beak, and not that eye-catching yellow. (See our full post on white throated sparrows.)

That should get you started...for more, browse posts about birds here on the Natural Capital, or check out the fantastic online guide at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Tuesday, August 28, 2012

Five Amazing Facts About Crows

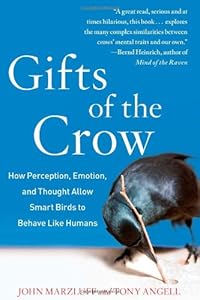

Crows are so common and well-known in our area that I've never bothered to write about them -- or really think much about them. I finally got around to reading a copy of Gifts of the Crow: How Perception, Emotion, and Thought Allow Smart Birds to Behave Like Humans that I received as a review copy, and am blown away.

Here are my top 5 amazing facts:

1. Crows display remarkable teamwork. You may have seen them mobbing a hawk to make it go away. They've also been seen to steal from other animals in pairs -- with one pulling a seagull's tail, say, while the other crow grabbing the tasty mollusk the seagull drops. And they have been seen to come to each other's aid, helping an injured crow walk to shelter.

2. Did you ever learn in elementary school that one of the things that separates humans from the animals is that humans use tools? Well, crows use tools. For example, this one figured out how to bend a wire into a hook to retrieve food.

3. Crows recognize faces, remember the behavior of the people with those faces, and pass on knowledge of the faces to other crows. If a person wearing a certain mask does something to threaten or annoy a crow, anyone wearing that mask in the future will be scolded and harrassed by crows in the area.

4. Crows are very persistent. One Seattle resident spent a day shooing crows away from a robin's nest in his yard (crows steal and eat eggs). For a year, scolding crows followed the man to the bus stop every workday, sometimes dive-bombing and hitting him in the head. When he moved to a new house 20 blocks away, he left at three in the morning to be sure the crows were asleep and wouldn't start pestering him at his new location.

5. A raven saying "Nevermore" is actually possible. Crows and ravens have been known to learn short words and phrases. Some even appear to understand the context of human language: one responded "what?" when its owner called it by name; one would say "Hello, Bob" only to its owner Bob; one would reply to "that's for you" with "that's for me."

There's much more detail on how crows do this, and possible reasons why, in Gifts of the Crow. Have you observed any cool crow behavior? We'd love to hear about it.

Here are my top 5 amazing facts:

1. Crows display remarkable teamwork. You may have seen them mobbing a hawk to make it go away. They've also been seen to steal from other animals in pairs -- with one pulling a seagull's tail, say, while the other crow grabbing the tasty mollusk the seagull drops. And they have been seen to come to each other's aid, helping an injured crow walk to shelter.

2. Did you ever learn in elementary school that one of the things that separates humans from the animals is that humans use tools? Well, crows use tools. For example, this one figured out how to bend a wire into a hook to retrieve food.

3. Crows recognize faces, remember the behavior of the people with those faces, and pass on knowledge of the faces to other crows. If a person wearing a certain mask does something to threaten or annoy a crow, anyone wearing that mask in the future will be scolded and harrassed by crows in the area.

4. Crows are very persistent. One Seattle resident spent a day shooing crows away from a robin's nest in his yard (crows steal and eat eggs). For a year, scolding crows followed the man to the bus stop every workday, sometimes dive-bombing and hitting him in the head. When he moved to a new house 20 blocks away, he left at three in the morning to be sure the crows were asleep and wouldn't start pestering him at his new location.

5. A raven saying "Nevermore" is actually possible. Crows and ravens have been known to learn short words and phrases. Some even appear to understand the context of human language: one responded "what?" when its owner called it by name; one would say "Hello, Bob" only to its owner Bob; one would reply to "that's for you" with "that's for me."

There's much more detail on how crows do this, and possible reasons why, in Gifts of the Crow. Have you observed any cool crow behavior? We'd love to hear about it.

Wednesday, May 9, 2012

LOOK FOR: Migratory Warblers

In the last 2 years, we've had a bunch of migrating warblers come through our yard in mid-May. In fact, we've noted four of the same species two years in a row. I like to think they remember our little pond as a nice stopping-over point (but I'm sure it's just random).

Have you seen any of these birds lately? I'm keeping an eye out to see if this will be the third year in a row for our backyard guests.

Blackpoll warblerCanada warblerCommon Yellowthroat American RedstartYellow-rumped warblerNorthern WaterthrushFor birdsongs, see the warbler list at the fantastic All About Birds.

Have you seen any of these birds lately? I'm keeping an eye out to see if this will be the third year in a row for our backyard guests.

Blackpoll warblerCanada warblerCommon Yellowthroat American RedstartYellow-rumped warblerNorthern WaterthrushFor birdsongs, see the warbler list at the fantastic All About Birds.

Thursday, March 29, 2012

Avian Architecture

**** I'm giving away a copy of this book! Details at the end of the post. ****

Over the last week I've been watching robins hop around my yard, picking out old plant stalks and other bits and pieces to build their nests. There's a pair working on a nest in the rose trellis over our front sidewalk -- always an exciting location, because we can watch the parents feed their babies from our porch. Plus, every time someone passes through our front gate a bird comes flying out!

Most nests are a little harder to see. They're usually in out-of-the-way places, and sometimes fiercely protected -- as I once learned when some mockingbirds built a nest in my hedge (I was seriously concerned for a minute there that my eyes would get pecked out). And actually, it's bad when humans get too close to bird nests anyway -- some species will abandon a nest if they are too bothered by the intrusion.

Peter Goodfellow gives us a better look in his book Avian Architecture, which won the 2011 American Publishers Awards for Professional and Scholarly Excellence (The PROSE Awards) in Popular Science & Popular Mathematics.

Just take a moment to marvel at the diversity of bird nests. They range in complexity from the barely-there scrapes in the ground of the arctic tern to the elaborately woven nest of the oropendula; they range in size from the super-tiny cup nest of the ruby-throated hummingbird to the six-foot-deep and six-foot-wide nest of the African white stork.

In addition to grasses and twigs, birds use rocks, mud, cacti, lichen, dandelion seeds, caterpillar silk, animal hairs, and spiderwebs to build their nests. Most surprising, perhaps, is the edible-nest swiftlet, which makes its nest entirely out of spit.

Goodfellow categorizes this diversity into 12 basic architectural styles: platforms, cups, domes, holes and tunnels, scrapes, mounds, bowers, colonies, aquatic nests, mud nests, hanging and woven nests, and edible nests.

Each section of the book includes "blueprint" line drawings for archetypal examples of the style, followed by short case studies on the materials and techniques birds use (examples here). The building technique pages are my favorites: the step-by-step drawings of how birds actually put a nest together really bring to life how much effort goes into the process.

My one complaint is that in seeking the diversity of nests from around the world, the book includes a relative scarcity of birds from our region. Of over 80 species illustrated in the book, only 13 are native to the mid-Atlantic.

My neighbors the robins make an appearance, but I have to say their nest architecture pales in comparison to some of the other locals Goodfellow picks:

The giveaway:

Princeton University Press sent me a free review copy of this book, and I'd like to pass it on to one of you. There are two ways to enter:

1. Go to our Facebook page and "share" one of our recent posts.

2. Go to our Twitter feed and retweet one of our tweets.

Deadline is midnight on Friday, April 6. If you're selected I'll contact you to ask for your address.

Don't win the giveaway? Your local library probably has a copy. If you buy the book through this link the Natural Capital gets a small commission.

the Natural Capital gets a small commission.

Over the last week I've been watching robins hop around my yard, picking out old plant stalks and other bits and pieces to build their nests. There's a pair working on a nest in the rose trellis over our front sidewalk -- always an exciting location, because we can watch the parents feed their babies from our porch. Plus, every time someone passes through our front gate a bird comes flying out!

Most nests are a little harder to see. They're usually in out-of-the-way places, and sometimes fiercely protected -- as I once learned when some mockingbirds built a nest in my hedge (I was seriously concerned for a minute there that my eyes would get pecked out). And actually, it's bad when humans get too close to bird nests anyway -- some species will abandon a nest if they are too bothered by the intrusion.

Peter Goodfellow gives us a better look in his book Avian Architecture, which won the 2011 American Publishers Awards for Professional and Scholarly Excellence (The PROSE Awards) in Popular Science & Popular Mathematics.

Just take a moment to marvel at the diversity of bird nests. They range in complexity from the barely-there scrapes in the ground of the arctic tern to the elaborately woven nest of the oropendula; they range in size from the super-tiny cup nest of the ruby-throated hummingbird to the six-foot-deep and six-foot-wide nest of the African white stork.

In addition to grasses and twigs, birds use rocks, mud, cacti, lichen, dandelion seeds, caterpillar silk, animal hairs, and spiderwebs to build their nests. Most surprising, perhaps, is the edible-nest swiftlet, which makes its nest entirely out of spit.

Goodfellow categorizes this diversity into 12 basic architectural styles: platforms, cups, domes, holes and tunnels, scrapes, mounds, bowers, colonies, aquatic nests, mud nests, hanging and woven nests, and edible nests.

Each section of the book includes "blueprint" line drawings for archetypal examples of the style, followed by short case studies on the materials and techniques birds use (examples here). The building technique pages are my favorites: the step-by-step drawings of how birds actually put a nest together really bring to life how much effort goes into the process.

My one complaint is that in seeking the diversity of nests from around the world, the book includes a relative scarcity of birds from our region. Of over 80 species illustrated in the book, only 13 are native to the mid-Atlantic.

My neighbors the robins make an appearance, but I have to say their nest architecture pales in comparison to some of the other locals Goodfellow picks:

- The bald eagle builds an 8-foot wide platform nest that can weigh two tons and last for over 50 years.

- The nest of a ruby-throated hummingbird is held together with spiderwebs, and is "smaller than a shot glass."

- Red-winged blackbirds weave their cup nests around the stems of plants that are growing in the water, giving eggs protection from land-based predators.

- Cliff swallows build colonies of tube-shaped nests out of mud attached to a rock wall.

- The Baltimore oriole makes about 10,000 stitches to weave a nest that hangs down from the branches of a tree.

The giveaway:

Princeton University Press sent me a free review copy of this book, and I'd like to pass it on to one of you. There are two ways to enter:

1. Go to our Facebook page and "share" one of our recent posts.

2. Go to our Twitter feed and retweet one of our tweets.

Deadline is midnight on Friday, April 6. If you're selected I'll contact you to ask for your address.

Don't win the giveaway? Your local library probably has a copy. If you buy the book through this link

Thursday, November 10, 2011

LOOK FOR: Starlings

You know I stick mostly to native species on this blog. There are so many wonderful creatures and plants to explore without needing to focus on the imported counterparts that are crowding them out. But a friend forwarded a beautiful little video that I thought I would pass along, because this truly is one of the natural phenomena that takes my breath away a few times a year.

Starlings were brought to the United States in the late 19th century by a group called the American Acclimitization Society, whose sole purpose was introducing European species of plants and animals. A sub-project of this larger work was to introduce into New York city parks every species of bird mentioned in a work of Shakespeare.

And what did Shakespeare think of starlings? They won't shut up. (Those of you who've been near a flock will agree.) In Henry IV, the king was refusing to pay a ransom to release his brother-in-law Edmund Mortimer. Hotspur, who took the prisoners in a battle, says:

He said he would not ransom Mortimer;

Forbad my tongue to speak of Mortimer;

But I will find him when he lies asleep,

And in his ear I'll holla 'Mortimer!'

Nay, I'll have a starling shall be taught to speak

Nothing but 'Mortimer,' and give it him

To keep his anger still in motion.

I don't think Hotspur ever went through with this plan, but the Acclimitization Society's dreams were fulfilled beyond their wildest expectations. It's estimated there are now more than 200 million starlings in North America, reaching coast to coast and into Canada and Mexico. The Introduced Species Summary Project complains that besides being noisy and messy, they ravage crops and crowd out native bird species as they travel around in flocks that sometimes number in the thousands.

Invasive though they are, such big flocks can also be a thing of beauty. Check it out.

Starlings were brought to the United States in the late 19th century by a group called the American Acclimitization Society, whose sole purpose was introducing European species of plants and animals. A sub-project of this larger work was to introduce into New York city parks every species of bird mentioned in a work of Shakespeare.

And what did Shakespeare think of starlings? They won't shut up. (Those of you who've been near a flock will agree.) In Henry IV, the king was refusing to pay a ransom to release his brother-in-law Edmund Mortimer. Hotspur, who took the prisoners in a battle, says:

He said he would not ransom Mortimer;

Forbad my tongue to speak of Mortimer;

But I will find him when he lies asleep,

And in his ear I'll holla 'Mortimer!'

Nay, I'll have a starling shall be taught to speak

Nothing but 'Mortimer,' and give it him

To keep his anger still in motion.

I don't think Hotspur ever went through with this plan, but the Acclimitization Society's dreams were fulfilled beyond their wildest expectations. It's estimated there are now more than 200 million starlings in North America, reaching coast to coast and into Canada and Mexico. The Introduced Species Summary Project complains that besides being noisy and messy, they ravage crops and crowd out native bird species as they travel around in flocks that sometimes number in the thousands.

Invasive though they are, such big flocks can also be a thing of beauty. Check it out.

Murmuration from Sophie Windsor Clive on Vimeo.

Friday, July 1, 2011

LOOK FOR: Bald Eagles

Matt and I were driving down the Beltway not too long ago when we realized a bald eagle was flying overhead. That this is even possible is such a potent reminder of how far these birds have come in our lifetime.

When I was born, bald eagles were on the brink of extinction. In the early 1970s, there were only about 400 nesting pairs recorded in the lower 48 states. They were one of the original species listed when the Endangered Species List was created in 1973.

With that legal protection from hunting and habitat destruction, plus the banning of DDT in 1972, bald eagles have made an amazing recovery. By 2007, it was estimated that there were more than 10,000 nesting pairs in the continental US -- enough that they were removed from the Endangered Species List that year. (They're still protected by the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act.)

Bald eagles like to nest near water (they eat fish). They avoid nesting near buildings and people -- with the exception of a few city slickers, including some who have nested in the District. With these requirements, and with each nesting pair defending a territory of about 250 acres, their nesting options are limited. But there are a few protected waterfront locations around the DC metro area that suit bald eagles just fine. We see an eagle almost every time we go to Jug Bay, for example. Farther afield, Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge on Maryland's Eastern Shore is reported to have a population of over a hundred eagles.

Eagles are the largest bird of prey you're likely to see near Washington, DC: they have a 6+ foot wingspan. They take their name from their all-white head (in Latin, too: Haliaeetus leucocephalus means sea eagle with a white (leukos) head (cephalus)). But for me, what really distinguishes them in flight is the all-white tail. Ospreys are smaller and have a mostly-white head, but not that white tail.

Keep an eye out anywhere along the Potomac or the Anacostia (check out our list of places to rent a canoe) and let us know if there's a spot where you see them!

For guaranteed sightings, Meadowside Nature Center in Rockville has an injured eagle that they care for. The National Zoo normally does too, but apparently their eagle area is under construction right now.

Happy Fourth of July!

When I was born, bald eagles were on the brink of extinction. In the early 1970s, there were only about 400 nesting pairs recorded in the lower 48 states. They were one of the original species listed when the Endangered Species List was created in 1973.

With that legal protection from hunting and habitat destruction, plus the banning of DDT in 1972, bald eagles have made an amazing recovery. By 2007, it was estimated that there were more than 10,000 nesting pairs in the continental US -- enough that they were removed from the Endangered Species List that year. (They're still protected by the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act.)

Bald eagles like to nest near water (they eat fish). They avoid nesting near buildings and people -- with the exception of a few city slickers, including some who have nested in the District. With these requirements, and with each nesting pair defending a territory of about 250 acres, their nesting options are limited. But there are a few protected waterfront locations around the DC metro area that suit bald eagles just fine. We see an eagle almost every time we go to Jug Bay, for example. Farther afield, Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge on Maryland's Eastern Shore is reported to have a population of over a hundred eagles.

Eagles are the largest bird of prey you're likely to see near Washington, DC: they have a 6+ foot wingspan. They take their name from their all-white head (in Latin, too: Haliaeetus leucocephalus means sea eagle with a white (leukos) head (cephalus)). But for me, what really distinguishes them in flight is the all-white tail. Ospreys are smaller and have a mostly-white head, but not that white tail.

Keep an eye out anywhere along the Potomac or the Anacostia (check out our list of places to rent a canoe) and let us know if there's a spot where you see them!

For guaranteed sightings, Meadowside Nature Center in Rockville has an injured eagle that they care for. The National Zoo normally does too, but apparently their eagle area is under construction right now.

Happy Fourth of July!

Friday, May 6, 2011

When it all comes together

We've lived in this house for six years. In that time, we've removed grass and weeds from probably 5000 square feet, planted hundreds of plants, and hauled many, many truckloads of leaf mulch from the Takoma Park DPW. This is not a complaint...it is good work, restorative work for us and for this tiny piece of land. (Plus, it serves as propagation for our landscaping business.)

All this time, we've also been studying the world of nature: reading books and going on walks with other people who know about lots of cool stuff and looking things up for this blog...and just watching and listening and spending lots of time outdoors.

And then, sometimes, everything just seems to come together.

The flowers are blooming, and a sphinx moth is feeding on them.

Woodpeckers are visiting the feeder. (They've found something nearby to drum on that has the timbre of a marimba, much better than the metallic tone of our gutters.)

A bess beetle comes out from under its log and starts walking across the yard.

A yellow-rumped warbler stops by to take a bath in our pond.

And an oriole comes and starts taking nesting material from the old flowerstalks.

Somehow, knowing what all this stuff is makes us appreciate it all the much more. We know how hard it can be to spot an oriole since they're usually up in the tree canopy. We know that funny drumming noise is probably one of the woodpeckers that we've been feeding. We know that the sphinx moth's larval host plant was probably the muscadine grape vine in our garden.

And all this, dear friends, is another reason I love writing this blog every week. I hope we've helped you appreciate something you've seen this spring a little more by knowing something more about it. We'd love to hear about it.

All this time, we've also been studying the world of nature: reading books and going on walks with other people who know about lots of cool stuff and looking things up for this blog...and just watching and listening and spending lots of time outdoors.

And then, sometimes, everything just seems to come together.

The flowers are blooming, and a sphinx moth is feeding on them.

Woodpeckers are visiting the feeder. (They've found something nearby to drum on that has the timbre of a marimba, much better than the metallic tone of our gutters.)

A bess beetle comes out from under its log and starts walking across the yard.

A yellow-rumped warbler stops by to take a bath in our pond.

And an oriole comes and starts taking nesting material from the old flowerstalks.

Somehow, knowing what all this stuff is makes us appreciate it all the much more. We know how hard it can be to spot an oriole since they're usually up in the tree canopy. We know that funny drumming noise is probably one of the woodpeckers that we've been feeding. We know that the sphinx moth's larval host plant was probably the muscadine grape vine in our garden.

And all this, dear friends, is another reason I love writing this blog every week. I hope we've helped you appreciate something you've seen this spring a little more by knowing something more about it. We'd love to hear about it.

Wednesday, March 30, 2011

The New Crossley Bird Guide: A Review & Your Chance to Meet the Author

There's a new bird ID guide out, and all the bird blogs are talking about it. I figured I'd join in, since the publisher was kind enough to send me a review copy. Even better, author Richard Crossley will be giving a free lecture and booksigning at the Audubon Naturalist Society's Woodend Sanctuary on Tuesday April 5, at 7:30-9:30pm.

But should you buy a copy of his Crossley's ID Guide? Let's take a look.

The basic approach of this guide is to offer a nearly full-page image (smaller for less common birds) made up of numerous photographs of a single bird species. I can't even imagine how much work must have gone into this: the book's website boasts that 10,000 photographs went into making these 640 plates. Stop and think about that for a second.

Things I like

Diversity of images. With many, many photos per bird, you get them at different angles, in flight, and engaging in some of their more common behaviors. You get close-ups and distance shots -- Crossley argues these tiny shots are most similar to how you'll see most birds. You also get a wider variation in color than many guides show: adults and juveniles, males and females, sun and shade, winter and summer, and even some molting birds.

Emphasis on behavior and habitat. Crossley really emphasizes that these things, along with shape and size, give you more information than color will about the bird you're looking at. The text is dwarfed by the images, but there's a lot in there.

How to Be a Better Birder. The introduction has a very nice section whose philosophy resonated with me a lot. "Knowing the name of a bird is not important, but knowing how to look at it is crucial."

Where's Waldo? Built into the approach of this book is a game for all ages: many birds are well hidden in the composite images. You could spend hours looking for them all. And it would probably make you a better birder in real life.

Things I don't like

My head is about to explode. These composite pictures are not for the faint of heart: dozens of bird images have been photoshopped together onto one background, often bringing trees or other perches with them. Many backgrounds have key habitat features, but some are just needlessly busy. For example, putting a crazy pink flowering cherry behind the cardinals really doesn't add useful information. (The rainbow behind the northern goshawks is simple enough to be a nice touch, though.)

Hard to navigate. Crossley argues that since taxonomy changes all the time, most organizational schemes become quickly outdated. But 183 pages of songbirds without a subheading? I'm overwhelmed. The rows and rows of thumbnail pictures in the front don't help much. I may add some sticky notes to help me page through.

Geographic range. This book includes everything east of the Rockies in "eastern." That will be a plus to some readers, but it adds to the overwhelming: there are a lot of birds in here that we will never see anywhere near the DC area. Roadrunners, anyone?

Bottom line

This is not a guide you'll take into the field: it's the size of a college textbook. And having just started with it, I get the feeling it could serve the same purpose. It has found a place on my bedside table, not with the field guides: it's a book I hope to look at carefully, studying pictures ahead of time. I'm imprinting these pictures on my brain so that I'll know more birds when I see them, without having to look them up.

Alternatively, the heft of this book could encourage you to learn to look at birds the way Crossley learned as a child: to make detailed notes in the field, then look up information when you get home. That forces you to really look at a bird, rather than focusing on finding the name and moving on. On the page and in the field, this book should help encourage you to really look.

The Crossley ID Guide: Eastern Birds

Princeton University Press, March 2011

544 pages, 7.5x10 inches

Buy a copy (and support the Natural Capital through this link)

(and support the Natural Capital through this link)

Read more reviews: Audubon magazine, 10,000 Birds, the Birder's Library, the Drinking Bird, the Birdchaser, Avian Review

Visit Crossley's website

But should you buy a copy of his Crossley's ID Guide? Let's take a look.

The basic approach of this guide is to offer a nearly full-page image (smaller for less common birds) made up of numerous photographs of a single bird species. I can't even imagine how much work must have gone into this: the book's website boasts that 10,000 photographs went into making these 640 plates. Stop and think about that for a second.

Things I like

Diversity of images. With many, many photos per bird, you get them at different angles, in flight, and engaging in some of their more common behaviors. You get close-ups and distance shots -- Crossley argues these tiny shots are most similar to how you'll see most birds. You also get a wider variation in color than many guides show: adults and juveniles, males and females, sun and shade, winter and summer, and even some molting birds.

Emphasis on behavior and habitat. Crossley really emphasizes that these things, along with shape and size, give you more information than color will about the bird you're looking at. The text is dwarfed by the images, but there's a lot in there.

How to Be a Better Birder. The introduction has a very nice section whose philosophy resonated with me a lot. "Knowing the name of a bird is not important, but knowing how to look at it is crucial."

Where's Waldo? Built into the approach of this book is a game for all ages: many birds are well hidden in the composite images. You could spend hours looking for them all. And it would probably make you a better birder in real life.

Things I don't like

My head is about to explode. These composite pictures are not for the faint of heart: dozens of bird images have been photoshopped together onto one background, often bringing trees or other perches with them. Many backgrounds have key habitat features, but some are just needlessly busy. For example, putting a crazy pink flowering cherry behind the cardinals really doesn't add useful information. (The rainbow behind the northern goshawks is simple enough to be a nice touch, though.)

Hard to navigate. Crossley argues that since taxonomy changes all the time, most organizational schemes become quickly outdated. But 183 pages of songbirds without a subheading? I'm overwhelmed. The rows and rows of thumbnail pictures in the front don't help much. I may add some sticky notes to help me page through.

Geographic range. This book includes everything east of the Rockies in "eastern." That will be a plus to some readers, but it adds to the overwhelming: there are a lot of birds in here that we will never see anywhere near the DC area. Roadrunners, anyone?

Bottom line

This is not a guide you'll take into the field: it's the size of a college textbook. And having just started with it, I get the feeling it could serve the same purpose. It has found a place on my bedside table, not with the field guides: it's a book I hope to look at carefully, studying pictures ahead of time. I'm imprinting these pictures on my brain so that I'll know more birds when I see them, without having to look them up.

Alternatively, the heft of this book could encourage you to learn to look at birds the way Crossley learned as a child: to make detailed notes in the field, then look up information when you get home. That forces you to really look at a bird, rather than focusing on finding the name and moving on. On the page and in the field, this book should help encourage you to really look.

The Crossley ID Guide: Eastern Birds

Princeton University Press, March 2011

544 pages, 7.5x10 inches

Buy a copy

Read more reviews: Audubon magazine, 10,000 Birds, the Birder's Library, the Drinking Bird, the Birdchaser, Avian Review

Visit Crossley's website

Friday, March 11, 2011

LOOK FOR: Woodcocks (or Timberdoodles)

Woodcocks are funny-looking birds with a shorebird's long beak and a big eye that looks a little misplaced. People have given them all kinds of silly names: mudbat, bogsucker, and -- perhaps most celebrated -- timberdoodle.

Most people will never see a woodcock, let alone worry about what to call one. They're mostly quiet during the day. They hang out on the ground, where they blend in so well with leaves and dry grasses that you might walk right past one and never notice. More likely, they're in a moist area that you're not going to walk through anyway (thus the "bogsucker" nickname).

But every spring, the male of this retiring species puts on a show. At twilight, he starts on the ground with a funny, buzzy noise that birders describe as a peent. Then he flies up 200+ feet in the air, and dives back down again, zigging and zagging, wings whistling as he goes. He'll repeat the whole thing several times in an evening. Other males will join in, all trying to outdo each other and attract the ladies.

This video gives some sense of what it's like, though there's a lot more waiting involved:

Woodcocks often return to the same mating grounds every year, so local birding groups can help you find them. Last year groups went out just about every week in March. Check our calendar for listings -- and also the longer list of groups below the calendar.

Want to try finding a bird on your own? Here's a great video from Sharon Stiteler of Birdchick on how she looks for woodcocks:

Let us know if you have any luck timberdoodling!

Most people will never see a woodcock, let alone worry about what to call one. They're mostly quiet during the day. They hang out on the ground, where they blend in so well with leaves and dry grasses that you might walk right past one and never notice. More likely, they're in a moist area that you're not going to walk through anyway (thus the "bogsucker" nickname).

But every spring, the male of this retiring species puts on a show. At twilight, he starts on the ground with a funny, buzzy noise that birders describe as a peent. Then he flies up 200+ feet in the air, and dives back down again, zigging and zagging, wings whistling as he goes. He'll repeat the whole thing several times in an evening. Other males will join in, all trying to outdo each other and attract the ladies.

This video gives some sense of what it's like, though there's a lot more waiting involved:

Woodcocks often return to the same mating grounds every year, so local birding groups can help you find them. Last year groups went out just about every week in March. Check our calendar for listings -- and also the longer list of groups below the calendar.

Want to try finding a bird on your own? Here's a great video from Sharon Stiteler of Birdchick on how she looks for woodcocks:

Let us know if you have any luck timberdoodling!

Friday, March 4, 2011

LOOK FOR: Migrating Canada Geese

I've mentioned before that Matt and I keep a nature journal where we write down the dates that we see things. And every year, for the last 3 years since we've been keeping this journal, we've written down that we saw large numbers of Canada geese migrating on March 7-9.

Let's see if the dates hold again this year. Leave a comment on this post when you see your first big flock migrating!

Of course, in this area, you can see Canada geese year-round. They love the combination of mowed grass and water, which you get on the Mall, the C&O canal, and suburban parks, golf courses, and developments. It's believed many of these non-migrating geese are the descendants of geese that were re-introduced after the species was over-hunted in the early 1900s.

But plenty of geese have not been taken in by the city life and remain totally wild, flying thousands of miles every year. They breed in Canada and spend their winters in the southern US and northern Mexico. These are the geese we see in large v-shaped flocks, flying north, at this time of year. Keep an ear out for their honking, so you can wish them safe travels on their journey.

Let's see if the dates hold again this year. Leave a comment on this post when you see your first big flock migrating!

Of course, in this area, you can see Canada geese year-round. They love the combination of mowed grass and water, which you get on the Mall, the C&O canal, and suburban parks, golf courses, and developments. It's believed many of these non-migrating geese are the descendants of geese that were re-introduced after the species was over-hunted in the early 1900s.

But plenty of geese have not been taken in by the city life and remain totally wild, flying thousands of miles every year. They breed in Canada and spend their winters in the southern US and northern Mexico. These are the geese we see in large v-shaped flocks, flying north, at this time of year. Keep an ear out for their honking, so you can wish them safe travels on their journey.

Friday, February 18, 2011

LOOK FOR: Backyard Birds (and count them)

The Great Backyard Bird Count is an annual event that takes a massive snapshot of where birds are in North America. In 2010, volunteers reported on a mind-boggling 11.2 million birds. I did it for the first time last year, and it gave me a warm fuzzy feeling to be part of something so huge.

Here's all it takes to participate in this weekend's count:

House Sparrow (66% of lists)

Passer domesticus

6.25 inches

If you've got a birdfeeder, you've got house sparrows. These birds were brought over from Europe sometime in the mid-1800s and have proceeded to make quite a home for themselves. Males have a lighter breast with black patch on their throat; females are plain and brown.

Northern Cardinal (66% of lists)

Cardinalis cardinalis

8.75 inches

There's something about a bright red bird that makes people happy. But female cardinals are pretty too: a hard-to-define mix of tan, red, and orange, with a bright orange bill. You'll often hear both sexes making short "chip" noises to check on each other.

Mourning Dove (64% of lists)

Zenaida macroura

12 inches

What color is a mourning dove? A brownish-grey, with pink undertones in the breast and maybe some blue if the light hits it right. We almost always see them in pairs or groups, walking around in our yard or perched on the utility lines, where they show off their long tails. Their song is in fact mournful sounding.

European Starling (50% of lists)

Sturnus vulgaris

8.5 inches

This bird is another import that has become widespread. Every once in a while a huge flock lands in our yard to forage, then disappears again. Starlings are smaller than crows, and their beaks are longer and thinner. Juveniles are covered in small white flecks, which make a beautiful pattern.

American Robin (43% of lists)

Turdus migratorius

10 inches

Everyone knows the robin, but you can amuse your friends by learning the Latin name for this bird (my brother in law calls out "turdus!" every time he sees one). Some robins spend the winter in our area, so they're not necessarily a sign of spring -- though they do become more plentiful as it starts to warm up.

Downy Woodpecker (43% of lists)

Picoides pubescens

6.75 inches

Downies are our smallest woodpecker. I was surprised to see this bird on the list as frequently as robins, but we do see them almost every day on our peanut bird feeder. Males have that red spot on the back of their head; in females it's just white.

House Finch (41% of lists)

Carpodacus mexicanus

6 inches

We used to have a pair of house finches that visited our windowboxes in Dupont Circle and delighted us with their sweet songs and the splash of color on the male's head. These birds are the third import on our list; they're native to the western US, but someone brought them east in the 1950s.

Chickadee (41% of lists)

Poecile carolinensis/atricapilla

5 inches

Chickadees are the shortest, roundest birds on our list: fluffy balls of cuteness that fly from tree to tree looking for insects. Washington DC is in the overlap of the range of two hard-to-distinguish species; Carolina chickadees are smaller than their black-capped cousins.

Dark-eyed Junco (40% of lists)

Junco hyemalis

6.25 inches

Juncos are snowbirds -- and Washington is part of their southern winter home. When it warms up a little more, they'll be off for Canada. For now, look carefully for these grey or grey-brown birds on the ground: they can blend in quite sneakily. (See our full post on juncos)

White-throated Sparrow (39% of lists)

Zonotrichia albicollis

6.75 inches

White-throated sparrows are another winter resident of the DC area. If one thing surprised me more than seeing the tiny yellow patches on this sparrow's head for the first time, it was learning that it's named for the white patch just under its beak, and not that eye-catching yellow. (See our full post on white throated sparrows.)

That should get you started...for more, browse posts about birds here on the Natural Capital, or check out the fantastic online guide at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Here's all it takes to participate in this weekend's count:

- Look for birds for at least 15 minutes on February 18-21. You can count anywhere; it doesn't actually have to be a backyard.

- Keep track of the species that you see, and for each species, the largest number that you see together simultaneously.

- Enter the information on the GBBC website.

House Sparrow (66% of lists)

Passer domesticus

6.25 inches

If you've got a birdfeeder, you've got house sparrows. These birds were brought over from Europe sometime in the mid-1800s and have proceeded to make quite a home for themselves. Males have a lighter breast with black patch on their throat; females are plain and brown.

Northern Cardinal (66% of lists)

Cardinalis cardinalis

8.75 inches

There's something about a bright red bird that makes people happy. But female cardinals are pretty too: a hard-to-define mix of tan, red, and orange, with a bright orange bill. You'll often hear both sexes making short "chip" noises to check on each other.

Mourning Dove (64% of lists)

Zenaida macroura

12 inches

What color is a mourning dove? A brownish-grey, with pink undertones in the breast and maybe some blue if the light hits it right. We almost always see them in pairs or groups, walking around in our yard or perched on the utility lines, where they show off their long tails. Their song is in fact mournful sounding.

European Starling (50% of lists)

Sturnus vulgaris

8.5 inches

This bird is another import that has become widespread. Every once in a while a huge flock lands in our yard to forage, then disappears again. Starlings are smaller than crows, and their beaks are longer and thinner. Juveniles are covered in small white flecks, which make a beautiful pattern.

American Robin (43% of lists)

Turdus migratorius

10 inches

Everyone knows the robin, but you can amuse your friends by learning the Latin name for this bird (my brother in law calls out "turdus!" every time he sees one). Some robins spend the winter in our area, so they're not necessarily a sign of spring -- though they do become more plentiful as it starts to warm up.

Downy Woodpecker (43% of lists)

Picoides pubescens

6.75 inches

Downies are our smallest woodpecker. I was surprised to see this bird on the list as frequently as robins, but we do see them almost every day on our peanut bird feeder. Males have that red spot on the back of their head; in females it's just white.

House Finch (41% of lists)

Carpodacus mexicanus

6 inches

We used to have a pair of house finches that visited our windowboxes in Dupont Circle and delighted us with their sweet songs and the splash of color on the male's head. These birds are the third import on our list; they're native to the western US, but someone brought them east in the 1950s.

Chickadee (41% of lists)

Poecile carolinensis/atricapilla

5 inches

Chickadees are the shortest, roundest birds on our list: fluffy balls of cuteness that fly from tree to tree looking for insects. Washington DC is in the overlap of the range of two hard-to-distinguish species; Carolina chickadees are smaller than their black-capped cousins.

Dark-eyed Junco (40% of lists)

Junco hyemalis

6.25 inches

Juncos are snowbirds -- and Washington is part of their southern winter home. When it warms up a little more, they'll be off for Canada. For now, look carefully for these grey or grey-brown birds on the ground: they can blend in quite sneakily. (See our full post on juncos)

White-throated Sparrow (39% of lists)

Zonotrichia albicollis

6.75 inches

White-throated sparrows are another winter resident of the DC area. If one thing surprised me more than seeing the tiny yellow patches on this sparrow's head for the first time, it was learning that it's named for the white patch just under its beak, and not that eye-catching yellow. (See our full post on white throated sparrows.)

That should get you started...for more, browse posts about birds here on the Natural Capital, or check out the fantastic online guide at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)