If you can go to Great Falls in the next couple of days, it's worth the trip. Call ahead to make sure trails are open: the water level is likely to rise before it falls. On Wednesday, the MD boardwalk to the falls was closed (towpath was open) but the VA side was all open -- and amazing.

The DC area definitely dodged the worst of this storm -- there's a post on the VA side of Great Falls showing how much higher the water has gotten in the past. This is really nothing in comparison. And yet it's still a dizzying amount of water. Huge logs are floating downstream. The familiar landscape of rocks is almost completely covered. And it's all moving so FAST.

We also stopped by Carderock to check out the Billy Goat C trail -- which is completely underwater in many places:

I hope you all get a chance to get out and enjoy ever-changing nature soon...be safe!

Getting outside, inside the beltway: tips on getting outdoors in the Washington, DC area.

Most Popular Posts

-

Photo credit: ilkerender Last year we listed places to swim near DC and places to rent a canoe near DC . Today we return to complete the s...

-

Summer calls out for being on the water. We've found more than a dozen locations where you can rent a canoe or kayak in the Washington, ...

-

What a lovely break in the heat we're having. Here are some things to keep an eye out for in August. Links are to previous LOOK FOR post...

-

This spring has been cold and a little slow, like last year. Morels , in particular, are just starting to show up. Below are all the things ...

-

The Jack in the pulpits are starting to unfurl right now. I've always loved these flowers, showy in their design rather than their color...

-

I've been distracted from the Natural Capital but I haven't totally forgotten about you guys...Here are some of the other things we ...

-

This time last year, the wood frogs were out and had already laid their eggs. As of this morning, the pond where we always find them was com...

-

Our monthly roundup of things to look for this month: Photo credit: InspiredinDesMoines I originally wrote about bald eagles for t...

-

Two of the things we love best about living in the DC metro area are the public transportation system, and the parks. And so, one of our mai...

-

If I had to name my biggest frustration with the nature around DC, the lack of good swimming holes might top the list. Until 7th grade I liv...

Showing posts with label October. Show all posts

Showing posts with label October. Show all posts

Thursday, November 1, 2012

Friday, October 21, 2011

Can You Name These 10 Autumn Leaves?

I picked up these leaves around the neighborhood this week. How many can you name?

Answers are at the bottom of this post.

How did you do? Hard to do from a photo? Get out there and enjoy the leaves this weekend, in person!

1. Mulberry 2.Beech 3. Dogwood 4. White oak 5. Redbud 6. Tuliptree 7. Pin oak 8. Spicebush 9. Sugar maple 10. Sycamore

Answers are at the bottom of this post.

How did you do? Hard to do from a photo? Get out there and enjoy the leaves this weekend, in person!

1. Mulberry 2.Beech 3. Dogwood 4. White oak 5. Redbud 6. Tuliptree 7. Pin oak 8. Spicebush 9. Sugar maple 10. Sycamore

Thursday, October 7, 2010

Things to Look For in October

With the weather we've been having, there's no question that fall is here. These are some of the things we love to look for in October:

Wild Grapes are tart but tasty trailside treats -- if you can reach them. We had some at Carderock in September; have you found any lately?

Acorns are littering the forest floor -- though not as many as last year, when they were clearly masting. We've been playing around with making acorn flour: take off the shells, grind the nutmeats into coarse flour, then put them in a coffee filter and run cold water through the flour repeatedly, until it's not bitter anymore. Then dry. Use it to replace a little flour in any baking recipe that doesn't require a lot of gluten. We love it in pancakes.

Virginia Creeper has started to turn a brilliant red in some places. It's the harbinger of fall color.

New England Asters are lighting up our backyard right now, and on a sunny day they're covered in pollinators. Do you have a favorite spot that they grow in the wild? We'd love to hear about it.

Cedar waxwings are beautiful but gluttonous birds that come through our yard every fall and feast on our holly berries. I love to find them by their high-pitched calls, which you can hear on a video in our post.

Wild Grapes are tart but tasty trailside treats -- if you can reach them. We had some at Carderock in September; have you found any lately?

Acorns are littering the forest floor -- though not as many as last year, when they were clearly masting. We've been playing around with making acorn flour: take off the shells, grind the nutmeats into coarse flour, then put them in a coffee filter and run cold water through the flour repeatedly, until it's not bitter anymore. Then dry. Use it to replace a little flour in any baking recipe that doesn't require a lot of gluten. We love it in pancakes.

Virginia Creeper has started to turn a brilliant red in some places. It's the harbinger of fall color.

New England Asters are lighting up our backyard right now, and on a sunny day they're covered in pollinators. Do you have a favorite spot that they grow in the wild? We'd love to hear about it.

Cedar waxwings are beautiful but gluttonous birds that come through our yard every fall and feast on our holly berries. I love to find them by their high-pitched calls, which you can hear on a video in our post.

Thursday, November 5, 2009

LOOK FOR: Witch Hazel, the Last Flowers of the Year

As one of the last things in the DC area to flower in the fall, witch hazel has a special place in my heart. It's not that the flowers are particularly showy -- the petals are just small yellow wisps, really. But the flowers of Hamamelis virginiana start blooming in October, and can keep going until Thanksgiving or even later.

Witch hazel (or witchhazel) is an understory shrub that grows up to 20 feet tall. Its flowers are about a half-inch to an inch wide, and they come in clusters of 3-5, on a little stalk coming off the twigs of the shrub. They'll form clusters of seedpods which explode when they're ripe, shooting their seeds up to 30 feet away. You may see some seedpods on the tree at the same time as the flowers are blooming.

There's another native species of witch hazel that, rather being the last to bloom this year, will be one of the first blooms of next year. Hamemelis vernalis often has redder flowers, and they're slightly smaller. We've never seen it in the wild, so let us know if you see some this winter! There are also Asian species of Hamemelis that are often planted ornamentally that flower in the winter.

Many people have heard of witch hazel because the bark and leaves have a long history of medicinal use as an astringent. But the "witch hazel" you can now buy in a store actually has very little witch hazel in it. It's made by soaking the leaves or bark in water, distilling it, then adding alcohol. People disagree on whether witch hazel actually has any effectiveness after the distillation process -- it may be the alcohol that's doing most of the good when you use this product. We've never tried making our own -- this tree just isn't common enough to justify it.

In the wild: Witch hazel likes moist soil, though we've also seen it on dry mountainsides. They're scattered along the Valley Trail in Rock Creek Park -- on our last hike we noticed several directly across Rock Creek from Picnic Area 8 that were in bloom. There used to be a nice stand of small witch hazels on the Rachel Carson trail north of Colesville Road, but a couple of years ago they were taken out by beavers. We'll have to check on whether they've managed to come back.

In your yard: Garden books recommend them, but the witch hazel we planted a few years ago still seems to struggle in the summer. All trees want a lot of water in their first year after planting, but this one perhaps more so.

Where have you seen witch hazel in the DC area? Leave us a comment below.

Photo credit: Jim Frazier

Witch hazel (or witchhazel) is an understory shrub that grows up to 20 feet tall. Its flowers are about a half-inch to an inch wide, and they come in clusters of 3-5, on a little stalk coming off the twigs of the shrub. They'll form clusters of seedpods which explode when they're ripe, shooting their seeds up to 30 feet away. You may see some seedpods on the tree at the same time as the flowers are blooming.

There's another native species of witch hazel that, rather being the last to bloom this year, will be one of the first blooms of next year. Hamemelis vernalis often has redder flowers, and they're slightly smaller. We've never seen it in the wild, so let us know if you see some this winter! There are also Asian species of Hamemelis that are often planted ornamentally that flower in the winter.

Many people have heard of witch hazel because the bark and leaves have a long history of medicinal use as an astringent. But the "witch hazel" you can now buy in a store actually has very little witch hazel in it. It's made by soaking the leaves or bark in water, distilling it, then adding alcohol. People disagree on whether witch hazel actually has any effectiveness after the distillation process -- it may be the alcohol that's doing most of the good when you use this product. We've never tried making our own -- this tree just isn't common enough to justify it.

In the wild: Witch hazel likes moist soil, though we've also seen it on dry mountainsides. They're scattered along the Valley Trail in Rock Creek Park -- on our last hike we noticed several directly across Rock Creek from Picnic Area 8 that were in bloom. There used to be a nice stand of small witch hazels on the Rachel Carson trail north of Colesville Road, but a couple of years ago they were taken out by beavers. We'll have to check on whether they've managed to come back.

In your yard: Garden books recommend them, but the witch hazel we planted a few years ago still seems to struggle in the summer. All trees want a lot of water in their first year after planting, but this one perhaps more so.

Where have you seen witch hazel in the DC area? Leave us a comment below.

Friday, October 30, 2009

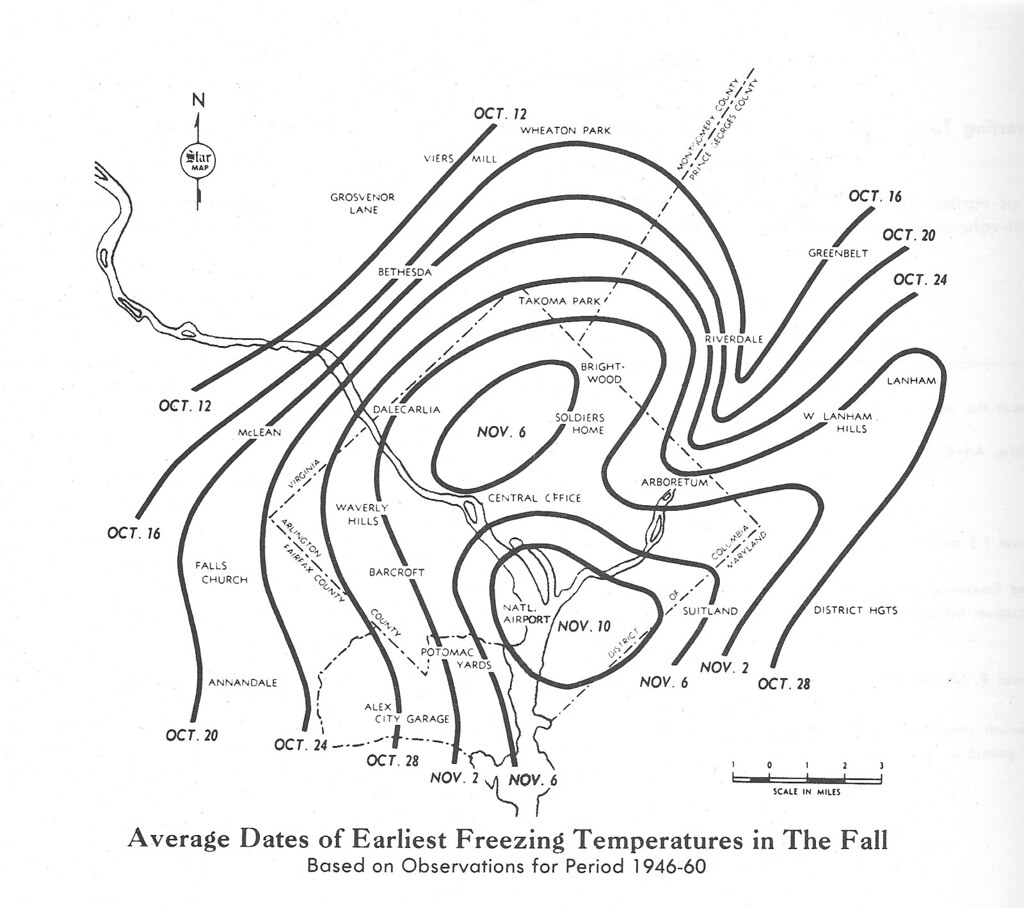

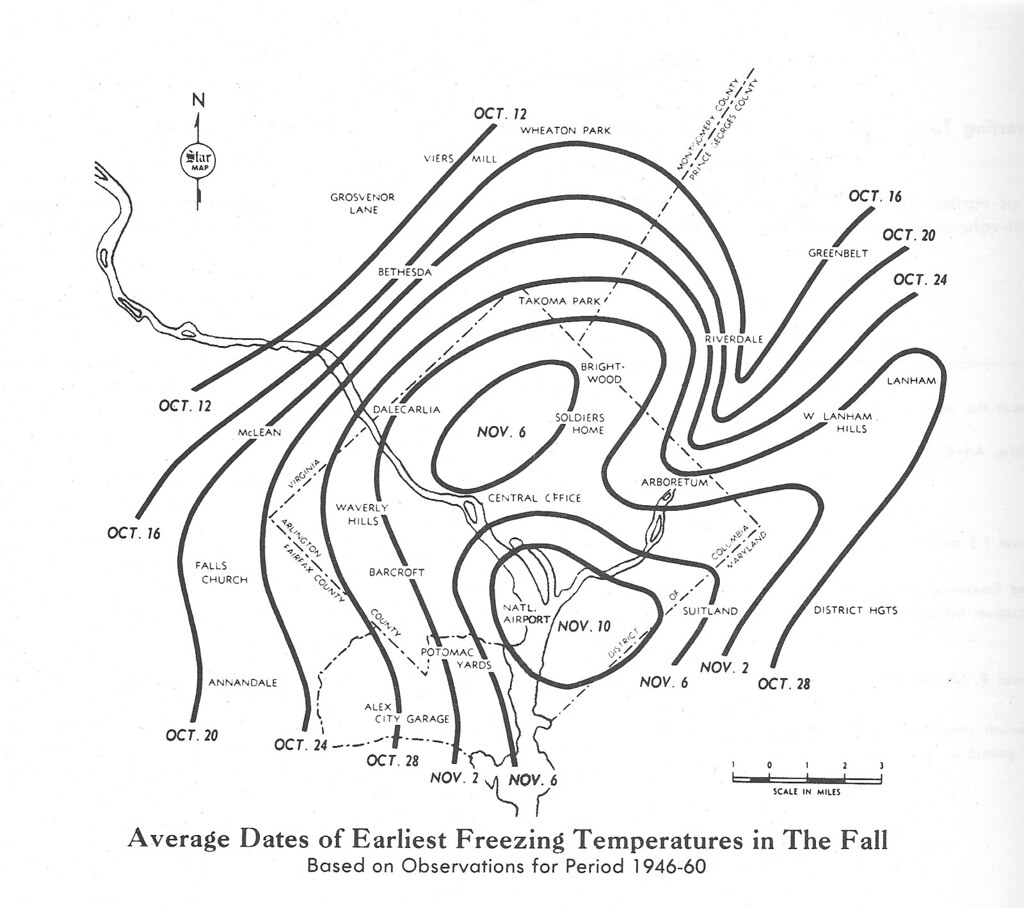

First Freezes and Heat Islands

As gardeners, we've always been quite aware of the national maps of hardiness zones and first frost dates. On these maps, the DC metro area is generally lumped with the surrounding regions, which have an average first frost date sometime between October 15 and October 31.

But downtown DC actually tends to freeze even later. In fact, we were sad to note that we lost almost a week off the end of our growing season just by moving from Dupont Circle to Silver Spring. This map, taken from The Washington Star Garden Book: The Encyclopedia of Gardening for the Chesapeake & Potomac Region by Deborah R. Fialka, shows a very localized picture of the average first freeze (I suspect these dates would be shifted later using more recent data):

by Deborah R. Fialka, shows a very localized picture of the average first freeze (I suspect these dates would be shifted later using more recent data):

What's going on in this picture? Two things: topography and urbanity. The area by National Airport, where the Potomac and the Anacostia meet, is the lowest-lying area in Washington, DC, and it freezes later than anywhere else in the metro area. The other oval on the map corresponds roughly with the Rock Creek valley.

Other than these river valleys, though, there's something else going on. There are circles radiating out from DC not just because of altitude, but also because there is a higher density of buildings and pavement in downtown DC. And those create what's known as an "urban heat island," trapping heat. It's enough to change the weather.

Folks worried about global warming think one way to slow down climate change is to address some of the factors that create urban heat islands. For one, street trees can keep the sun off of pavement, so that it doesn't heat up as much. Likewise, green roofs and highly reflective roofs can keep buildings from absorbing so much heat.

In the meantime, you can observe the subtle differences in nature that stem from these temperature differences. Do the trees drop their leaves a little later in one place vs. another? Do flowers last longer in the fall or come up earlier in the spring? Keep an eye out, and let us know what you see.

Thanks to Flickr user DCTropics for the map!

But downtown DC actually tends to freeze even later. In fact, we were sad to note that we lost almost a week off the end of our growing season just by moving from Dupont Circle to Silver Spring. This map, taken from The Washington Star Garden Book: The Encyclopedia of Gardening for the Chesapeake & Potomac Region

What's going on in this picture? Two things: topography and urbanity. The area by National Airport, where the Potomac and the Anacostia meet, is the lowest-lying area in Washington, DC, and it freezes later than anywhere else in the metro area. The other oval on the map corresponds roughly with the Rock Creek valley.

Other than these river valleys, though, there's something else going on. There are circles radiating out from DC not just because of altitude, but also because there is a higher density of buildings and pavement in downtown DC. And those create what's known as an "urban heat island," trapping heat. It's enough to change the weather.

Folks worried about global warming think one way to slow down climate change is to address some of the factors that create urban heat islands. For one, street trees can keep the sun off of pavement, so that it doesn't heat up as much. Likewise, green roofs and highly reflective roofs can keep buildings from absorbing so much heat.

In the meantime, you can observe the subtle differences in nature that stem from these temperature differences. Do the trees drop their leaves a little later in one place vs. another? Do flowers last longer in the fall or come up earlier in the spring? Keep an eye out, and let us know what you see.

Thanks to Flickr user DCTropics for the map!

Thursday, October 29, 2009

LOOK FOR: Cedar Waxwings

Cedar waxwings are gorgeous birds. Most of their plumage is muted brownish-grey, which doesn't sound so interesting, I know, but they're so silky-looking that their latin name, Bombycilla, comes from the Greek for silk, bombux.

Adding a little intrigue, their slight crest and black face mask can give them a Donnie Brasco-meets-Batman look. And then, if you can get close enough, you'll see a striking yellow bar on the bottom of their tail, and (on most birds) a few bright red dots of wax on the wings.

Cedar waxwings rely on small fruits and berries for over 80 percent of their diet, though they supplement their spring and summer diet with insects when fruits are scarce. They travel in flocks, and a flock will often completely devour the berries of a tree before moving on to their next spot.

In fact, these birds have quite a reputation for gluttony. Audubon once noted that waxwings “gorge themselves to such excess as sometimes to be unable to fly...I have seen some which, although wounded and confined to a cage, have eaten of apples until suffocation deprived them of life.” Perhaps it's not surprising, then, that their courtship rituals revolve around food: the male brings a berry or an insect to a female, and they pass it back and forth several times before the female finally eats it.

We usually hear cedar waxwings before we see them. Their calls are a soft, high-pitched whistle; in a flock, the noise can be fairly continuous. This video from YouTube has a good example:

In the wild: Cedar waxwings like forest edges. Their numbers are actually increasing, possibly because suburban landscapes offer lots of edge-like habitat. Keep an ear out for their whistling, and an eye out for large flocks of birds eating tree fruits.

In your yard: The best way to attract cedar waxwings is to plant native trees and shrubs that bear small fruits, including dogwood, serviceberry, cedar, hawthorn, cherry, winterberry, holly, mulberry, chokecherry, and hackberry. Research has found that more than half of cedar waxwing nests are in either maple or cedar trees.

Adding a little intrigue, their slight crest and black face mask can give them a Donnie Brasco-meets-Batman look. And then, if you can get close enough, you'll see a striking yellow bar on the bottom of their tail, and (on most birds) a few bright red dots of wax on the wings.

Cedar waxwings rely on small fruits and berries for over 80 percent of their diet, though they supplement their spring and summer diet with insects when fruits are scarce. They travel in flocks, and a flock will often completely devour the berries of a tree before moving on to their next spot.

In fact, these birds have quite a reputation for gluttony. Audubon once noted that waxwings “gorge themselves to such excess as sometimes to be unable to fly...I have seen some which, although wounded and confined to a cage, have eaten of apples until suffocation deprived them of life.” Perhaps it's not surprising, then, that their courtship rituals revolve around food: the male brings a berry or an insect to a female, and they pass it back and forth several times before the female finally eats it.

We usually hear cedar waxwings before we see them. Their calls are a soft, high-pitched whistle; in a flock, the noise can be fairly continuous. This video from YouTube has a good example:

In the wild: Cedar waxwings like forest edges. Their numbers are actually increasing, possibly because suburban landscapes offer lots of edge-like habitat. Keep an ear out for their whistling, and an eye out for large flocks of birds eating tree fruits.

In your yard: The best way to attract cedar waxwings is to plant native trees and shrubs that bear small fruits, including dogwood, serviceberry, cedar, hawthorn, cherry, winterberry, holly, mulberry, chokecherry, and hackberry. Research has found that more than half of cedar waxwing nests are in either maple or cedar trees.

Thursday, October 22, 2009

LOOK FOR: Wild Grapes

I had a book of Aesop's Fables as a child, and the story I remember best is the story of the Fox and the Grapes. There's a big, juicy bunch of grapes hanging from a vine, and a fox is trying as hard as he can to get to them, but just can't quite reach. When he gives up, the fox says, "I don't want those grapes anyway -- they're probably sour!"

Sounds like the wild grapes of ancient Greece weren't too different from our own -- very tempting but very sour. Our native grapes are also very small. But we like them anyway...and like the fox in Aesop's fable, we'll go to some lengths to get some every fall.

Before you try to eat wild grapes, be confident in your identification. The leaves can be quite varied in size and shape, but generally have roughly toothed edges. The leaves may have three distinct lobes, or they may just hint at them. The vines climb with distinctive, curly tendrils that wrap around whatever they can for support.

As they get older, the vines shed their bark, giving them a shredded texture. It's not uncommon to see thick, peeling grapevines reaching far up into the canopy -- they've kept pace with the tree they're hanging from, making sure they can get sun for their leaves even as the tree puts on new growth.

But you're looking for fruit that's within reach, which will likely be on younger vines. Clusters of wild grapes look something like miniature clusters of cultivated grapes. When ripe, they are dark purple, but (like cultivated grapes) they may have a blush of yeast on them that makes them look a little lighter. They have multiple crunchy seeds which take up a lot of the fruit. But the fruit that is there has an intense flavor.

There are several other small, purple fruits in the fall. Make sure you rule these out -- none of them are edible, and some are quite poisonous: virginia creeper (which has leaves made of five leaflets, and red stems on the fruit), Canada moonseed (whose leaves are a similar shape to grapes, but smooth, not toothed; each fruit has a single, moon-shaped seed), porcelain berry (also has grape-like leaves, but the berries are blue and white before ripening, not green like unripe grapes), and pokeweed (not a vine, but it can be mixed into thickets that also include grapes; fruits branch off a very straight stalk that's often reddish).

Enough warnings. We've taught 3-year-olds to reliably recognize wild grapes...you can do it too.

In the wild: Wild grapes need some sunlight to fruit well but they also like the support of trees. They generally thrive where there has been a disturbance in the forest canopy, or on the trees on the edge of a forest. There are tons of grapes out there that you have no hope of reaching, but every once in a while, a younger vine will have some fruit low enough for you to get a taste.

In your yard: Wild grapes are a lot easier to grow than cultivated grapes, in the sense that they don't get as many pests and diseases. But the vines can grow up to 75 feet long. They'll do best in full sun, on a trellis. You can also try a more naturalistic planting, as long as there's something for the tendrils to wrap around for support.

Sounds like the wild grapes of ancient Greece weren't too different from our own -- very tempting but very sour. Our native grapes are also very small. But we like them anyway...and like the fox in Aesop's fable, we'll go to some lengths to get some every fall.

Before you try to eat wild grapes, be confident in your identification. The leaves can be quite varied in size and shape, but generally have roughly toothed edges. The leaves may have three distinct lobes, or they may just hint at them. The vines climb with distinctive, curly tendrils that wrap around whatever they can for support.

As they get older, the vines shed their bark, giving them a shredded texture. It's not uncommon to see thick, peeling grapevines reaching far up into the canopy -- they've kept pace with the tree they're hanging from, making sure they can get sun for their leaves even as the tree puts on new growth.

But you're looking for fruit that's within reach, which will likely be on younger vines. Clusters of wild grapes look something like miniature clusters of cultivated grapes. When ripe, they are dark purple, but (like cultivated grapes) they may have a blush of yeast on them that makes them look a little lighter. They have multiple crunchy seeds which take up a lot of the fruit. But the fruit that is there has an intense flavor.

There are several other small, purple fruits in the fall. Make sure you rule these out -- none of them are edible, and some are quite poisonous: virginia creeper (which has leaves made of five leaflets, and red stems on the fruit), Canada moonseed (whose leaves are a similar shape to grapes, but smooth, not toothed; each fruit has a single, moon-shaped seed), porcelain berry (also has grape-like leaves, but the berries are blue and white before ripening, not green like unripe grapes), and pokeweed (not a vine, but it can be mixed into thickets that also include grapes; fruits branch off a very straight stalk that's often reddish).

Enough warnings. We've taught 3-year-olds to reliably recognize wild grapes...you can do it too.

In the wild: Wild grapes need some sunlight to fruit well but they also like the support of trees. They generally thrive where there has been a disturbance in the forest canopy, or on the trees on the edge of a forest. There are tons of grapes out there that you have no hope of reaching, but every once in a while, a younger vine will have some fruit low enough for you to get a taste.

In your yard: Wild grapes are a lot easier to grow than cultivated grapes, in the sense that they don't get as many pests and diseases. But the vines can grow up to 75 feet long. They'll do best in full sun, on a trellis. You can also try a more naturalistic planting, as long as there's something for the tendrils to wrap around for support.

Thursday, October 15, 2009

LOOK FOR: Acorns of many shapes and sizes - an identification guide for 12 common oak species

There are 90 species of oak in North America. Their acorns are an important food for a broad diversity of wildlife, from insects to deer. And historically, they were a staple food for Native Americans in this area.

Oaks are generally split into two groups: "red" and "white." Red oaks have leaves whose lobes come to a point, with a little bristle on each point. Their acorns take two years to mature, so even as they're dropping this year's crop, they've already got half-grown acorns for next year. White oaks have leaves with more rounded lobes, typically lighter-colored bark, and their acorns take only one year to mature. But even within those two groups, there's a wonderful diversity of acorn shapes and sizes. Below are a selection of some of the acorns you might see in the greater DC area. (We've tried to line them up so they're to scale.) How many can you find in the wild?

One way to really get familiar with acorns is to collect them for Growing Native. The Potomac Conservancy will use them to replant buffer zones along the Potomac and its tributaries. This improves water quality and provides important wildlife habitat. You can donate collected acorns until October 26 in Virginia and October 31 in Maryland and DC.

All photos by Steve Hurst at the amazing USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database, except the post oak acorns, which are from the magnificent old tree here at The Natural Capital headquarters.

Oaks are generally split into two groups: "red" and "white." Red oaks have leaves whose lobes come to a point, with a little bristle on each point. Their acorns take two years to mature, so even as they're dropping this year's crop, they've already got half-grown acorns for next year. White oaks have leaves with more rounded lobes, typically lighter-colored bark, and their acorns take only one year to mature. But even within those two groups, there's a wonderful diversity of acorn shapes and sizes. Below are a selection of some of the acorns you might see in the greater DC area. (We've tried to line them up so they're to scale.) How many can you find in the wild?

Red Oaks

White Oaks

|  |  |

| Northern Red Oak Quercus rubra | Southern red oak Quercus falcata | Black oak Quercus velutina |

|  |  |

| Willow Oak Quercus phellos | Pin oak Quercus palustris | Blackjack oak Quercus marilandica |

White Oaks

|  |  |

| White oak Quercus alba | Overcup oak Quercus lyrata | Swamp white oak Quercus bicolor |

|  |  |

| Chestnut oak Quercus prinus | Post oak Quercus stellata | Bur oak Quercus macrocarpa |

One way to really get familiar with acorns is to collect them for Growing Native. The Potomac Conservancy will use them to replant buffer zones along the Potomac and its tributaries. This improves water quality and provides important wildlife habitat. You can donate collected acorns until October 26 in Virginia and October 31 in Maryland and DC.

All photos by Steve Hurst at the amazing USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database, except the post oak acorns, which are from the magnificent old tree here at The Natural Capital headquarters.

Thursday, October 8, 2009

LOOK FOR: Bright Red Virginia Creeper

Virginia Creeper is one of the first signs of fall in the DC area. You should notice its leaves (each made of five leaflets, in a palmate form, alternating up the vine) turning red soon.

Virginia Creeper is one of the first signs of fall in the DC area. You should notice its leaves (each made of five leaflets, in a palmate form, alternating up the vine) turning red soon.The scientific name for Virginia Creeper, Parthenocissus quinquefolia, literally means "five-leaved virgin-ivy." (Perhaps starting the name with partheno, or virgin, was an old-school pun on the plant's common name.) Some people call it five-leaved ivy, though it's in a different family from the other "ivies" we know, and certainly won't make you itch like poison ivy (which, you'll remember, has three leaves).

But Virginia creeper and poison ivy do share the characteristic of turning red early in the fall. Most plants turn color simply because they're giving up on photosynthesis for the year, and they're losing the chlorophyll that turns their leaves green. But these vines have evolved to turn red a little earlier than they really need to. It turns out that they're colorful around the time that their berries are ripe, which serves as a loud announcement to birds to come and check them out. The extra advantage in seed spreading must be worth trading off for the extra bit of energy the plants might gain by photosynthesizing for a little longer.

In the wild: Virginia creeper grows throughout the DC metro area, and can live in many different environments -- sunny and shady, wet and dry. If you learn to spot it this fall while it's red, perhaps you'll it notice next year while it's green.

In the wild: Virginia creeper grows throughout the DC metro area, and can live in many different environments -- sunny and shady, wet and dry. If you learn to spot it this fall while it's red, perhaps you'll it notice next year while it's green.In your yard: Virginia creeper is considered fairly aggressive -- it can take over an area if you don't stay on top of it. But this characteristic can make it a good solution for an area that needs covering -- an ugly fence, a wall, or as William Cullina

Like the photos in this post? Mouse over for credits; a click takes you to the photographer on Flickr.

Thursday, September 24, 2009

LOOK FOR: Spicebush Berries

If you have ever been hiking in the woods in the DC area, chances are you've walked by hundreds of spicebush shrubs. They've got small yellow flowers in the spring, then they form a nondescript green backdrop in the woods for the rest of the summer. Until September -- when their berries turn bright red.

Spicebush can grow up to 20 feet tall, but we commonly see them at about 5-10 feet. The leaves have smooth edges and alternate along the branch. As fall progresses, the leaves will turn yellow. The berries may remain on the shrub after the leaves have fallen off, but the birds may get to them first.

The twigs, leaves, and berries of spicebush all have a smell reminiscent of nutmeg or allspice when crushed. Presumably, the Latin name Lindera benzoin was given as a reference to benzoin resin, which was used to make incense and perfume in Asia and Europe. It's actually more related to laurels, including the bay laurel that gives us bay leaves.

Spicebush parts don't just smell good -- you can use them as a spice. The twigs can be brewed in hot water to make tea. Berries can be used fresh or frozen, as an allspice substitute. (Steve Brill recommends against drying.) We'll often cook them up with sliced apples to make a delicious topping for pancakes. Each berry has a single seed inside, which can be ground up with the rest if you're going to use it as a spice -- that's a lot less work than trying to get the seed out of each one.

As you're looking for the berries, also take a peek if you see any leaves folded over. You might find the caterpillar of a spicebush swallowtail butterfly, whose only host plant is the spicebush. They're lovely black butterflies, but their caterpillars are adorable -- they have big eyespots that make them look like a cartoon snake. You might also find the caterpillar of a promethea silkmoth, a large and beautiful moth that we have seen far more as a cocoon hanging from spicebush than in any other stage of its life cycle.

In the wild: Spicebush is one of the dominant understory shrubs in our local forest. In Rock Creek Park, we recently noticed large groves on both sides of the Valley Trail, in the section east of Boundary Bridge.

In your yard: Spicebush need shade, but a few hours of sun will encourage them to flower more and set more fruit. They can also suffer if they get too dry, especially as they're getting established -- they'll do best with reasonably moist soil.

Matt keeps a little stock of spicebush seedlings to put into clients' yards. They regularly get eaten up by spicebush swallowtail caterpillars in the summer. Most bounce back from the damage -- after all, these caterpillars have been eating these bushes for millions of years. And we love supporting the butterflies!

Spicebush can grow up to 20 feet tall, but we commonly see them at about 5-10 feet. The leaves have smooth edges and alternate along the branch. As fall progresses, the leaves will turn yellow. The berries may remain on the shrub after the leaves have fallen off, but the birds may get to them first.

The twigs, leaves, and berries of spicebush all have a smell reminiscent of nutmeg or allspice when crushed. Presumably, the Latin name Lindera benzoin was given as a reference to benzoin resin, which was used to make incense and perfume in Asia and Europe. It's actually more related to laurels, including the bay laurel that gives us bay leaves.

Spicebush parts don't just smell good -- you can use them as a spice. The twigs can be brewed in hot water to make tea. Berries can be used fresh or frozen, as an allspice substitute. (Steve Brill recommends against drying.) We'll often cook them up with sliced apples to make a delicious topping for pancakes. Each berry has a single seed inside, which can be ground up with the rest if you're going to use it as a spice -- that's a lot less work than trying to get the seed out of each one.

As you're looking for the berries, also take a peek if you see any leaves folded over. You might find the caterpillar of a spicebush swallowtail butterfly, whose only host plant is the spicebush. They're lovely black butterflies, but their caterpillars are adorable -- they have big eyespots that make them look like a cartoon snake. You might also find the caterpillar of a promethea silkmoth, a large and beautiful moth that we have seen far more as a cocoon hanging from spicebush than in any other stage of its life cycle.

In the wild: Spicebush is one of the dominant understory shrubs in our local forest. In Rock Creek Park, we recently noticed large groves on both sides of the Valley Trail, in the section east of Boundary Bridge.

In your yard: Spicebush need shade, but a few hours of sun will encourage them to flower more and set more fruit. They can also suffer if they get too dry, especially as they're getting established -- they'll do best with reasonably moist soil.

Matt keeps a little stock of spicebush seedlings to put into clients' yards. They regularly get eaten up by spicebush swallowtail caterpillars in the summer. Most bounce back from the damage -- after all, these caterpillars have been eating these bushes for millions of years. And we love supporting the butterflies!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)